Evaluability (and Cheap Holiday Shopping)

❦

With the expensive part of the Hallowthankmas season now approaching, a question must be looming large in our readers’ minds:

“Dear Overcoming Bias, are there biases I can exploit to be seen as generous without actually spending lots of money?”

I’m glad to report the answer is yes! According to Hsee—in a paper entitled “Less is better: When low-value options are valued more highly than high-value options”—if you buy someone a $45 scarf, you are more likely to be seen as generous than if you buy them a $55 coat.1

This is a special case of a more general phenomenon. In an earlier experiment, Hsee asked subjects how much they would be willing to pay for a second-hand music dictionary:2

- Dictionary A, from 1993, with 10,000 entries, in like-new condition.

- Dictionary B, from 1993, with 20,000 entries, with a torn cover and otherwise in like-new condition.

The gotcha was that some subjects saw both dictionaries side-by-side, while other subjects only saw one dictionary…

Subjects who saw only one of these options were willing to pay an average of $24 for Dictionary A and an average of $20 for Dictionary B. Subjects who saw both options, side-by-side, were willing to pay $27 for Dictionary B and $19 for Dictionary A.

Of course, the number of entries in a dictionary is more important than whether it has a torn cover, at least if you ever plan on using it for anything. But if you’re only presented with a single dictionary, and it has 20,000 entries, the number 20,000 doesn’t mean very much. Is it a little? A lot? Who knows? It’s non-evaluable. The torn cover, on the other hand—that stands out. That has a definite affective valence: namely, bad.

Seen side-by-side, though, the number of entries goes from non-evaluable to evaluable, because there are two compatible quantities to be compared. And, once the number of entries becomes evaluable, that facet swamps the importance of the torn cover.

From Slovic et al.: Which would you prefer?3

- A 29/36 chance to win $2.

- A 7/36 chance to win $9.

While the average prices (equivalence values) placed on these options were $1.25 and $2.11 respectively, their mean attractiveness ratings were 13.2 and 7.5. Both the prices and the attractiveness rating were elicited in a context where subjects were told that two gambles would be randomly selected from those rated, and they would play the gamble with the higher price or higher attractiveness rating. (Subjects had a motive to rate gambles as more attractive, or price them higher, that they would actually prefer to play.)

The gamble worth more money seemed less attractive, a classic preference reversal. The researchers hypothesized that the dollar values were more compatible with the pricing task, but the probability of payoff was more compatible with attractiveness. So (the researchers thought) why not try to make the gamble’s payoff more emotionally salient—more affectively evaluable—more attractive?

And how did they do this? By adding a very small loss to the gamble. The old gamble had a 7/36 chance of winning $9. The new gamble had a 7/36 chance of winning $9 and a 29/36 chance of losing 5 cents. In the old gamble, you implicitly evaluate the attractiveness of $9. The new gamble gets you to evaluate the attractiveness of winning $9 versus losing 5 cents.

“The results,” said Slovic et al., “exceeded our expectations.” In a new experiment, the simple gamble with a 7/36 chance of winning $9 had a mean attractiveness rating of 9.4, while the complex gamble that included a 29/36 chance of losing 5 cents had a mean attractiveness rating of 14.9.

A follow-up experiment tested whether subjects preferred the old gamble to a certain gain of $2. Only 33% of students preferred the old gamble. Among another group asked to choose between a certain $2 and the new gamble (with the added possibility of a 5 cents loss), fully 60.8% preferred the gamble. After all, $9 isn’t a very attractive amount of money, but $9 / 5 cents is an amazingly attractive win/loss ratio.

You can make a gamble more attractive by adding a strict loss! Isn’t psychology fun? This is why no one who truly appreciates the wondrous intricacy of human intelligence wants to design a human-like AI.

Of course, it only works if the subjects don’t see the two gambles side-by-side.

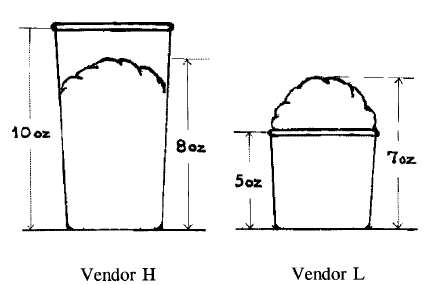

Similarly, which of these two ice creams do you think subjects in Hsee’s 1998 study preferred?

From Hsee, © 1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Naturally, the answer depends on whether the subjects saw a single ice cream, or the two side-by-side. Subjects who saw a single ice cream were willing to pay $1.66 to Vendor H and $2.26 to Vendor L. Subjects who saw both ice creams were willing to pay $1.85 to Vendor H and $1.56 to Vendor L.

What does this suggest for your holiday shopping? That if you spend $400 on a 16GB iPod Touch, your recipient sees the most expensive MP3 player. If you spend $400 on a Nintendo Wii, your recipient sees the least expensive game machine. Which is better value for the money? Ah, but that question only makes sense if you see the two side-by-side. You’ll think about them side-by-side while you’re shopping, but the recipient will only see what they get.

If you have a fixed amount of money to spend—and your goal is to display your friendship, rather than to actually help the recipient—you’ll be better off deliberately not shopping for value. Decide how much money you want to spend on impressing the recipient, then find the most worthless object which costs that amount. The cheaper the class of objects, the more expensive a particular object will appear, given that you spend a fixed amount. Which is more memorable, a $25 shirt or a $25 candle?

Gives a whole new meaning to the Japanese custom of buying $50 melons, doesn’t it? You look at that and shake your head and say “What is it with the Japanese?” And yet they get to be perceived as incredibly generous, spendthrift even, while spending only $50. You could spend $200 on a fancy dinner and not appear as wealthy as you can by spending $50 on a melon. If only there was a custom of gifting $25 toothpicks or $10 dust specks; they could get away with spending even less.

P.S.: If you actually use this trick, I want to know what you bought.

Christopher K. Hsee, “Less Is Better: When Low-Value Options Are Valued More Highly than High-Value Options,” Behavioral Decision Making 11 (2 1998): 107–121. ↩

Christopher K. Hsee, “The Evaluability Hypothesis: An Explanation for Preference Reversals between Joint and Separate Evaluations of Alternatives,” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 67 (3 1996): 247–257, doi:10.1006/obhd.1996.0077. ↩

Slovic et al., “Rational Actors or Rational Fools.” ↩