Friedrich Nietzsche

Have you not heard of that madman who lit a lantern in the bright morning hours, ran to the market-place, and cried incessantly: "I am looking for God! I am looking for God!"

As many of those who did not believe in God were standing together there, he excited considerable laughter. Have you lost him, then? said one. Did he lose his way like a child? said another. Or is he hiding? Is he afraid of us? Has he gone on a voyage? or emigrated? Thus they shouted and laughed. The madman sprang into their midst and pierced them with his glances.

"Where has God gone?" he cried. "I shall tell you. We have killed him - you and I. We are his murderers. But how have we done this? How were we able to drink up the sea? Who gave us the sponge to wipe away the entire horizon? What did we do when we unchained the earth from its sun? Whither is it moving now? Whither are we moving now? Away from all suns? Are we not perpetually falling? Backward, sideward, forward, in all directions? Is there any up or down left? Are we not straying as through an infinite nothing? Do we not feel the breath of empty space? Has it not become colder? Is it not more and more night coming on all the time? Must not lanterns be lit in the morning? Do we not hear anything yet of the noise of the gravediggers who are burying God? Do we not smell anything yet of God's decomposition? Gods too decompose. God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him. How shall we, murderers of all murderers, console ourselves? That which was the holiest and mightiest of all that the world has yet possessed has bled to death under our knives. Who will wipe this blood off us? With what water could we purify ourselves? What festivals of atonement, what sacred games shall we need to invent? Is not the greatness of this deed too great for us? Must we not ourselves become gods simply to be worthy of it? There has never been a greater deed; and whosoever shall be born after us - for the sake of this deed he shall be part of a higher history than all history hitherto."

Here the madman fell silent and again regarded his listeners; and they too were silent and stared at him in astonishment. At last he threw his lantern to the ground, and it broke and went out. "I have come too early," he said then; "my time has not come yet. The tremendous event is still on its way, still travelling - it has not yet reached the ears of men. Lightning and thunder require time, the light of the stars requires time, deeds require time even after they are done, before they can be seen and heard. This deed is still more distant from them than the distant stars - and yet they have done it themselves."

It has been further related that on that same day the madman entered divers churches and there sang a requiem. Led out and quietened, he is said to have retorted each time: "what are these churches now if they are not the tombs and sepulchres of God?"

Andy Weir

You were on your way home when you died.

It was a car accident. Nothing particularly remarkable, but fatal nonetheless. You left behind a wife and two children. It was a painless death. The EMTs tried their best to save you, but to no avail. Your body was so utterly shattered you were better off, trust me.

And that's when you met me.

"What… what happened?" You asked. "Where am I?"

"You died," I said, matter-of-factly. No point in mincing words.

"There was a… a truck and it was skidding…"

"Yup," I said.

"I… I died?"

"Yup. But don't feel bad about it. Everyone dies," I said.

You looked around. There was nothingness. Just you and me. "What is this place?" You asked. "Is this the afterlife?"

"More or less," I said.

"Are you god?" You asked.

"Yup," I replied. "I'm God."

"My kids… my wife," you said.

"What about them?"

"Will they be all right?"

"That's what I like to see," I said. "You just died and your main concern is for your family. That's good stuff right there."

You looked at me with fascination. To you, I didn't look like God. I just looked like some man. Or possibly a woman. Some vague authority figure, maybe. More of a grammar school teacher than the almighty.

"Don't worry," I said. "They'll be fine. Your kids will remember you as perfect in every way. They didn't have time to grow contempt for you. Your wife will cry on the outside, but will be secretly relieved. To be fair, your marriage was falling apart. If it's any consolation, she'll feel very guilty for feeling relieved."

"Oh," you said. "So what happens now? Do I go to heaven or hell or something?"

"Neither," I said. "You'll be reincarnated."

"Ah," you said. "So the Hindus were right,"

"All religions are right in their own way," I said. "Walk with me."

You followed along as we strode through the void. "Where are we going?"

"Nowhere in particular," I said. "It's just nice to walk while we talk."

"So what's the point, then?" You asked. "When I get reborn, I'll just be a blank slate, right? A baby. So all my experiences and everything I did in this life won't matter."

"Not so!" I said. "You have within you all the knowledge and experiences of all your past lives. You just don't remember them right now."

I stopped walking and took you by the shoulders. "Your soul is more magnificent, beautiful, and gigantic than you can possibly imagine. A human mind can only contain a tiny fraction of what you are. It's like sticking your finger in a glass of water to see if it's hot or cold. You put a tiny part of yourself into the vessel, and when you bring it back out, you've gained all the experiences it had.

"You've been in a human for the last 48 years, so you haven't stretched out yet and felt the rest of your immense consciousness. If we hung out here for long enough, you'd start remembering everything. But there's no point to doing that between each life."

"How many times have I been reincarnated, then?"

"Oh lots. Lots and lots. An in to lots of different lives." I said. "This time around, you'll be a Chinese peasant girl in 540 AD."

"Wait, what?" You stammered. "You're sending me back in time?"

"Well, I guess technically. Time, as you know it, only exists in your universe. Things are different where I come from."

"Where you come from?" You said.

"Oh sure," I explained "I come from somewhere. Somewhere else. And there are others like me. I know you'll want to know what it's like there, but honestly you wouldn't understand."

"Oh," you said, a little let down. "But wait. If I get reincarnated to other places in time, I could have interacted with myself at some point."

"Sure. Happens all the time. And with both lives only aware of their own lifespan you don't even know it's happening."

"So what's the point of it all?"

"Seriously?" I asked. "Seriously? You're asking me for the meaning of life? Isn't that a little stereotypical?"

"Well it's a reasonable question," you persisted.

I looked you in the eye. "The meaning of life, the reason I made this whole universe, is for you to mature."

"You mean mankind? You want us to mature?"

"No, just you. I made this whole universe for you. With each new life you grow and mature and become a larger and greater intellect."

"Just me?" What about everyone else?

"There is no one else," I said. "In this universe, there's just you and me."

You stared blankly at me. "But all the people on earth…"

"All you. Different incarnations of you."

"Wait. I'm everyone!?"

"Now you're getting it," I said, with a congratulatory slap on the back.

"I'm every human being who ever lived?"

"Or who will ever live, yes."

"I'm Abraham Lincoln?"

"And you're John Wilkes Booth, too," I added.

"I'm Hitler?" You said, appalled.

"And you're the millions he killed."

"I'm Jesus?"

"And you're everyone who followed him."

You fell silent.

"Every time you victimized someone," I said, "you were victimizing yourself. Every act of kindness you've done, you've done to yourself. Every happy and sad moment ever experienced by any human was, or will be, experienced by you."

You thought for a long time.

"Why?" You asked me. "Why do all this?"

"Because someday, you will become like me. Because that's what you are. You're one of my kind. You're my child."

"Whoa," you said, incredulous. "You mean I'm a god?"

"No. Not yet. You're a fetus. You're still growing. Once you've lived every human life throughout all time, you will have grown enough to be born."

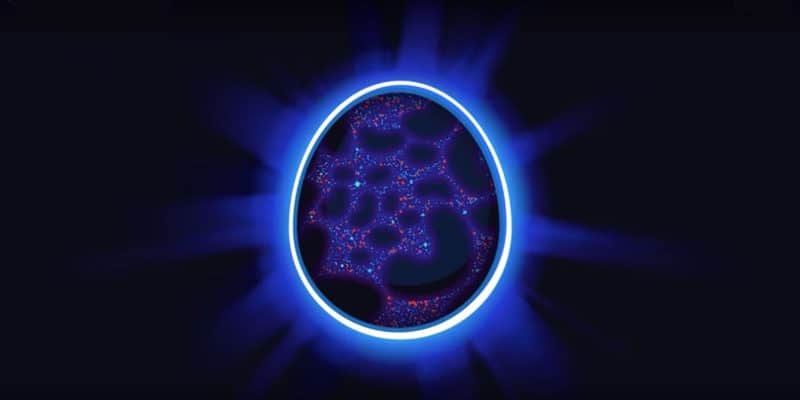

"So the whole universe," you said, "it's just…"

"An egg." I answered. "Now it's time for you to move on to your next life."

And I sent you on your way.

Søren Kierkegaard

Suppose there was a king who loved a humble maiden. The king was like no other king. Every statesman trembled before his power. No one dared breathe a word against him, for he had the strength to crush all opponents.

And yet this mighty king was melted by love for a humble maiden who lived in a poor village in his kingdom. How could he declare his love for her? In an odd sort of way, his kingliness tied his hands. If he brought her to the palace and crowned her head with jewels and clothed her body in royal robes, she would surely not resist-no one dared resist him. But would she love him?

She would say she loved him, of course, but would she truly? Or would she live with him in fear, nursing a private grief for the life she had left behind? Would she be happy at his side? How could he know for sure? If he rode to her forest cottage in his royal carriage, with an armed escort waving bright banners, that too would overwhelm her. He did not want a cringing subject. He wanted a lover, an equal. He wanted her to forget that he was a king and she a humble maiden and to let shared love cross the gulf between them. For it is only in love that the unequal can be made equal.

The king, convinced he could not elevate the maiden without crushing her freedom, resolved to descend to her. Clothed as a beggar, he approached her cottage with a worn cloak fluttering loose about him. This was not just a disguise – the king took on a totally new identity – He had renounced his throne to declare his love and to win hers.

David Foster Wallace

The soft plopping sounds. The slight gassy sounds. The little, involuntary, grunts. The special sigh of an older man at a urinal, the way he establishes himself there and sets his feet and aims and then lets out a timeless sigh you know he's not aware of. This was his environment. Six days a week he stood there. Saturdays a double shift. The needles-and-nails quality of urine into water. The unseen rustle of newspapers on bare laps. The odors.

Top-rated historic hotel in the state. The finest lobby, the single finest men's room between the two coasts, surely. Marble shipped from Italy. Stall doors of seasoned cherry. Since 1969 he's stood there. Rococo fixtures and scalloped basins. Opulent and echoing. A large opulent echoing room for men of business, substantial men, men with places to go and people to see. The odors. Don't ask about the odors. The difference between some men's odors, the sameness in all men's odors. All sounds amplified by tile and Florentine stone. The moans of the prostatic. The hiss of the sinks. The ripping extractions of deep-lying phlegm, the plosive and porcelain splat. The sounds of fine shoes on dolomite flooring. The inguinal rumbles. The hellacious ripping explosions of gas and the sound of stuff hitting the water. Half-atomized by pressures brought to bear. Solid, liquid, gas. All the odors. Odor as environment. All day.

Nine hours a day. Standing there in Good-Humor white. All sounds magnified, reverberating slightly. Men coming in, men going out. Eight stalls, six urinals, sixteen sinks. Do the math. What were they thinking?

It's what he stands in. In the sonic center. Where the shine stand used to be. In the crafted space between the end of the sinks and the start of the stalls. The space designed for him to stand. The vortex. Just outside the long mirror's frame; by the sinks—a continuous sink of Florentine marble, sixteen scalloped basins, leaves of gold foil around the fixtures, mirror of good Danish plate. In which men of substance drag material out of the corners of their eyes and squeeze their pores, blow their nose in the sinks and walk off without rinsing. He stood all day with his towels and small cases of personal-size toiletries. A trace of balsam in the three vents' whisper. The vents' threnody is inaudible unless the room is empty. He stands there when it's empty too. This is his occupation; this is his career. Dressed all in white like a masseur. Plain white Hanes T and white pants and tennis shoes he had to throw out if so much as a spot. He takes their cases and topcoats, guards them, remembers without asking whose is whose. Speaking as little as possible in all those acoustics. Appearing at men's elbows to hand them towels. An impassivity that is effacement. This is my father's career.

The stalls' fine doors end a foot from the floor—why is this? Why this tradition? Is it descended from animals' stalls? Is the word stall related to stable? Fine stalls that afford some visual privacy and nothing else. If anything they amplify the sounds inside, bullhorns on encl. You hear it all. The balsam makes the odors worse by sweetening them. The toes of dress shoes defiled along the row of spaces beneath the doors. The stalls full after lunch. A long rectangular box of shoes. Some tapping. Some of them humming, speaking aloud to themselves, forgetting they are not alone. The flatus and tussis and meaty splats. Defecation, egestion, extrusion, dejection, purgation, voidance. The unmistakable rumble of the toilet-paper dispensers. The occasional click of nail clippers or depilatory scissors. Effluence. Emission. Orduration, micturition, transudation, emiction, feculence, catharsis—so many synonyms—why? What are we trying to say to ourselves in so many ways?

The olfactory clash of different men's colognes, deodorants, hair tonic, mustache wax. The rich smell of the foreign and unbathed. Some of the stalls' shoes touching their mate hesitantly, tentatively, as if sniffing it. The damp lisp of buttocks shifting on padded seats. The tiny pulse of each bowl's pool. The little dottles that survive flushing. The urinals' ceaseless purl and trickle. The indole stink of putrefied food, the eccrine tang to the jackets, the uremic breeze that follows each flush. Men who flush toilets with their feet. Men who will touch fixtures only with tissue. Men who trail paper out of the stalls, their own comet's tail, the paper lodged in their aims. Anus. The word anus. The anuses of the well-to-do ranging above the bowls' water, flexing, puckering, distending. Soft faces squeezed tight in effort. Old men who require all kinds of ghastly help—lowering and arranging another man's shanks, wiping another man. Silent, wordless, impassive. Whisking the shoulders of another man, shaking off another man, removing a pubic hair from the pleat of another man's slacks. For coins. The sign says it all. Men who tip, men who do not tip. The effacement cannot be too complete or they forget he is there when it comes time to tip. The trick of his demeanor is to appear only provisionally there, to exist all and only if needed. Aid without intrusion. Service without servant. No man wants to know another man can smell him. Millionaires who do not tip. Natty men who splatter the bowls and tip a nickel. Heirs who steal towels. Tycoons who pick their noses with their thumb. Philanthropists who throw cigar butts on the floor. Self-made men who spit in the sink. Wildly rich men who do not flush and without a thought leave it to someone else to flush because this is literally what they are used to—the old saw Would you do this at home.

He bleached his work clothes himself, ironed them. Never a word of complaint. Impassive. The sort of man who stands in one place all day. Sometimes the very soles of the shoes visible under there, in the stalls, of vomiting men. The word vomit. The mere word. Men being ill in a room with acoustics. All the mortal sound he stood in every day. Try to imagine. The soft expletives of constipated men, men with colitis, ileus, irritable bowel, lientery, dyspepsia, diverticulitis, ulcers, bloody flux. Men with colostomies, handing him the bag to dispose of. An equerry of the human. Hearing without hearing. Seeing only need. The slight nod that in men's rooms is acknowledgment and deferral at once. The ghastly metastasized odors of continental breakfasts and business dinners. A double shift when he could. Food on the table, a roof, children to educate. His arches would swell from the standing. His bare feet were blancmanges. He showered thrice daily and scrubbed himself raw, but the job still followed him. Never a word.

The door tells the whole story. MEN. I haven't seen him since 1978 and I know he's still there, all in white, standing. Averting his eyes to preserve their dignity. But his own? His own five senses? What are those three monkeys' names? His task is to stand there as if he were not there. Not really. There's a trick to it. A special nothing you look at.

I didn't learn it in a men's room, I can tell you that.

by Robin Hanson

You are in a grocery store, and thinking of buying some meat. You think you know what buying and eating this meat would mean for your taste buds, your nutrition, and your pocketbook, and let's assume that on those grounds it looks like a good deal. But now you want to think about the morality of doing this, by which we usually mean that you want to consider what this means for others, such as animals. Aren't you hurting cows by eating beef, or pigs by eating pork?

Maybe you may think it obvious that you hurt animals by eating meat, but you still think you are justified in doing so. Or maybe you don't think such harm is justified, and so are a vegetarian. But I want to argue that, all things considered, you are not hurting animals; you are helping them.

First, notice that the cow or pig that once was the meat in front of you is already dead. So you can't hurt that animal much, except perhaps by violating its last wishes. But what about other cows and pigs? Doesn't buying more meat increase the overall demand for meat, and won't farms out there respond to this increased demand by killing more animals to send to grocery stores? So aren't you responsible for the killing of those animals?

Well not really. Farmers are going to kill pretty much all their grown animals no matter what the demand; they really don't have much else to do with the animals they raise for meat. But farmers will respond to changes in demand by changing the number of new animals they raise to kill later. So by buying more meat from the grocery store, you are responsible for more deaths of future farm animals.

But the alternative to those future animal lives cut short by butchery is not longer future animal lives. The alternative is that those animals will never have existed. People who buy less meat don't really spend less money on food overall, they mainly just spend more money on other non-meat food. This results in fewer pig farms and more asparagus farms, and pretty much the same overall amount of land devoted to farming. Creating more asparagus farms does not create more wilderness where wild animals can range free; this is not what asparagus farms do. So the real choice here is between creating pigs who live for a while and then are killed, and creating more asparagus plants.

If asparagus plants have little moral worth per se, our question then comes down to this: is it good or bad to create pigs who live for a while and then die? Well, is it good to create people that will eventually die? We usually say yes, if their lives are "worth living" overall. That is, if they get value out of being alive, and are not in a situation like severe torture, where they would rather be dead than alive. So are pigs lives worth living?

We might well agree that wild pigs have lives more worth living, per day at least, just as humans may be happier in the wild instead of fighting traffic to work in a cubical all day. But even these human lives are worth living, and it is my judgment that most farm animal's lives are worth living too. Most farm animals prefer living to dying; they do not want to commit suicide.

If so, the consequence to others of buying that meat in the grocery store, rather than asparagus, is good; you create farm animals whose lives are worth living. And thus the consequence of buying asparagus rather than meat is, by comparison, bad. So if you, like me, think your actions are more moral when you do more good for others, you should agree with me that meat is moral, and veggies are immoral.

There are two standard responses to the argument I've just given. The first response says that killing is just wrong, even when the consequences to others of doing so are good. The second response claims that in fact most farm animals live as if in torture, and so the animals would rather be dead than alive. By this account I guess killing existing farm animals is a kind merciful act, while creating new farm animals is cruel. If you have doubts on this point, I suggest you visit a farm.

Now it might make sense to be picky about how the farm animals that you eat were raised. It would be kind of you to pay a little more for your meat to improve the lives of the animals that become your meat. Just don't confuse a lack of extra kindness with cruelty; people already do more good by buying ordinary meat than by buying veggies.

How kind would it be to animals to spend more or less of your income on food? Changing your food budget might change the amount of land that is farmed, though this effect is weak because farmland can be used to produce non-food products. Corn, for example, may be used to produce ethanol. And if you do manage to induce less farmland and more wild land, you'll have to realize that, per land area, farms are more efficient at producing "higher" animals like pigs and cows. So there is a tradeoff between producing more farm animals with worse lives, or fewer wild animals with better lives, if in fact wild animals live better lives.